A New Kink in the Global Supply Chain

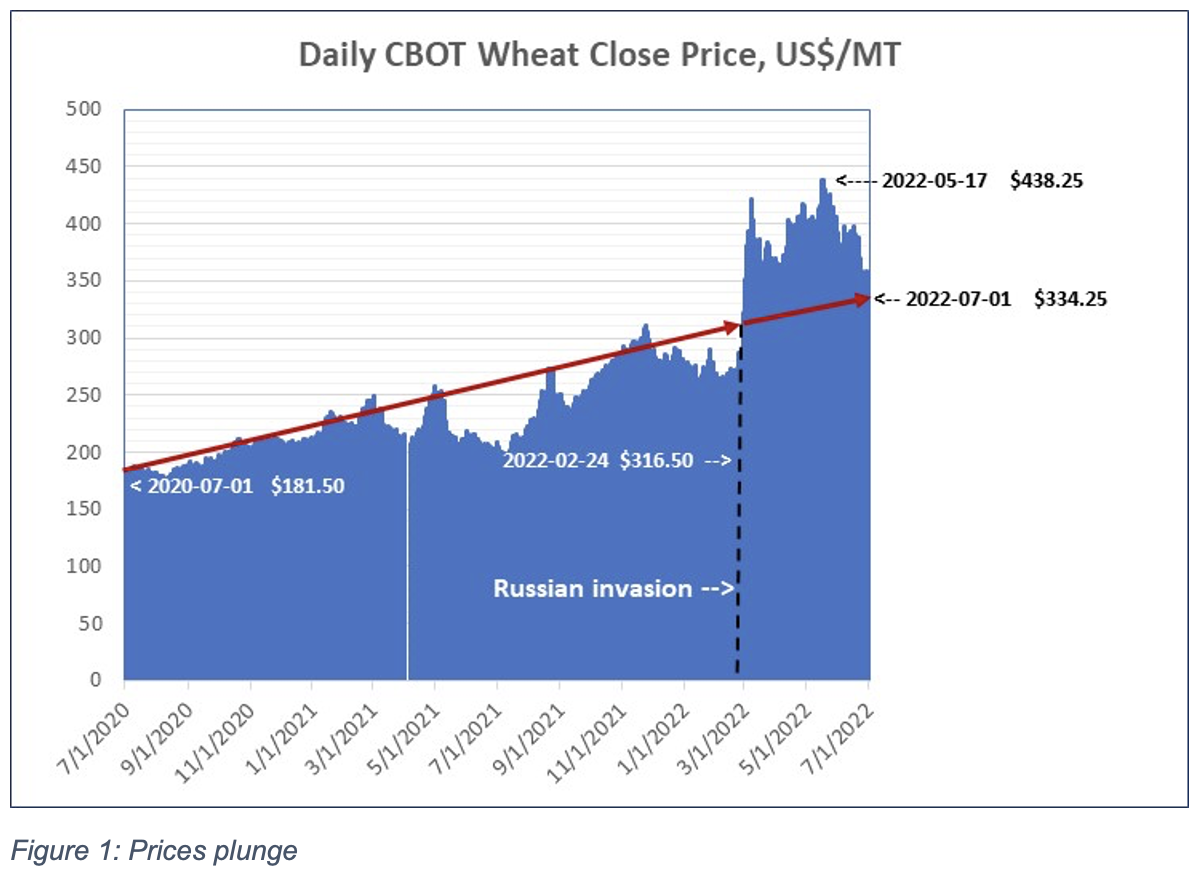

Adam Smith, the 18th century “Father” of the science of Economy described the countless dispersed individual decisions that move market prices as “unseen hands.” He was undoubtedly referring to events such as the unexpected price movements that we have witnessed in the agricultural commodity market, particularly during the last two weeks of June 2022. With no overt consolidation evident in the market’s outlook on future wheat, corn and soybean availability or demand, prices plunged. Wheat went from $438/mt on May 17, to $334 on July 1, more than a 20% drop. At that price, almost all the increases seen following the Russian invasion of Ukraine have been wiped out (see Figure 1).

Traders were left struggling to explain why and scrambling to cover positions. At least one Dubai-based trading house with links to Russia has allegedly defaulted on a 170,000 mt wheat delivery for July, unable to provide grain at current prices.

Although North American crop conditions appear slightly better than a month ago, there are still major global commodity availability uncertainties at-play, such as: extreme heat in Europe, India’s ability - or not - to export wheat, volatile Chinese demand, and continuing unmet needs of major grain importers (even though Egypt, Algeria and Jordan just accepted offers for more than 1.5 million tons of wheat in the last few days of June – see more on needs, below). And underlying much of these recent issues, Russia appears to be consolidating its presence in eastern Ukraine and is still able to impede stocks awaiting export from Ukraine. And yet, despite this, their loss of Snake Island (south of Odesa) may augur well for the eventual export of Ukrainian grain.

An intriguing insight into what is certainly not the only cause of both the initial rise in agriculture commodity prices back in 2020, and then in the plunging prices of June 2022, are the large movements of hedge funds into - and then more recently, out of - agricultural futures (see Figure 2). Do they sense a loss of momentum in pressures of commodity prices (which they contribute significantly to)?

In the meantime, the structure, conduct and performance of agricultural commodity trading has been greatly, and perhaps permanently, altered by all of the features noted above, plus the ubiquitous influences of climate change, the pandemic rebound, a globalization of trade, and the restless movements of countries seeking to assure their food security.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made reliance on these two preeminent exporters of the world’s grains and oilseeds a risky proposition. Fears of a global shortage of staple grains, as opposed to just high prices forcing the poor out of the market, seems not to be the issue now as other suppliers have stepped forward to meet needs.

Figure 3 shows both “winners” and “losers” of global export market share among major wheat and corn exporters, as seen via global maritime agricultural commodity shipping data (source: AgFlow). Despite its continuing ability to export grain through the Black Sea, even if in smaller bulk carriers, Russia has lost more than 6% of the global wheat/corn export market, down from near 25% to 18.7% (comparing January-June 2022 and January-June 2017-2021 maritime exports).

Ukraine has, of course, fared worse, losing 10% of its global market share, from 18% down to 8% (counting pre-invasion January and February 2022 exports, and reflecting its increasing ability to filter out new exports, largely through Romania).

“Winners” include Argentina (+11%), India (+4%), Australia (+2.8%), and finally, seen at the bottom of the table, exports from Russian-controlled Ukrainian ports which went from barely a .1% percent of the global total to now having a 1% market share.

But what of the importers, the consumers of these critical staple foods? Grain prices started a pronounced rise to historic levels back in 2020, and went even higher after the Russian invasion. High food prices inordinately and damagingly affect the poor, who generally spend more than half their income on food. Recognizing this, many governments try to subsidize high grain costs, which are generally associated with social upheaval and internal political instability, and several countries are teetering now on the brink of famine (Somalia, Ethiopia, Yemen). Others struggle to purchase daily food needs in a higher-priced market (Sri Lanka, Lebanon, Tunisia, Egypt).

Figure 4 shows a rough measure of whether countries which have traditionally relied (>20% of total wheat and corn imports) upon either Russia, or Ukraine, or both for their wheat and corn imports, have been able to import the same quantities of those grains as they normally import, even at the vastly higher prices that prevail now.

At the left-hand side of the graph are found countries that have imported more wheat and corn in the first 6 months of 2022 than they normally did in the same six-month period of the last 5-years (2017-2021). Immediately evident are the differences in the absolute quantity of imports required.

Egypt, Turkey, Iran and Indonesia import vastly greater quantities of these grains than all the others combined. Of these three, Egypt is only slightly above its five-year average, not considering the more than 3 million tons of wheat the state just procured from its farmers under required sales of the recent harvest; nor do these figures yet show a recent tender the country completed to purchase 800,000+ tons. Turkey has procured much more than it did on average over the previous 5 years, helped by an increased percentage of its wheat imports in 2022 coming from Russia (56% to 64%).

The three countries where most concern for inadequate imports should be given are Lebanon, Syria and (despite the small quantity involved) Somalia. Lebanon, which is close to a total collapse of state finances, has only procured about 40% of the wheat most of its population consumes as a primary part of their diet. Syria’s precarious war-torn economy is just meeting its previous averages, but internal distribution to those who need imported grain is likely not effective in meeting those needs. Somalia is right on the verge of its second famine in 10 years, and any shortfall of food will have deadly consequences. Sri Lanka, shown to the left of these three, is just meeting its previous wheat and corn import levels (rice is the staple in its diet), but the economic and political crisis it is currently in also merits extra concern for its food security.

Putting aside the cases noted above, which are true humanitarian emergencies, the other notable feature shown by the graphic is how successful most of the other countries have been in an expensive and disrupted export market to find and purchase more wheat and corn than they did on average over the last 5 years. This is likely due to the fact that the price crisis is more than two years old, and it forced importers to adopt more rigorous import habits well before the invasion.

It is important to accurately frame the real and damaging food security issues that have arisen as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. So far, sanctions on Russia have had a negative impact on its ability to export grains, but as seen above, most countries continue to find the wheat they need, and over time, Russia is increasing its ability to export its crops.

What the world loses due to Ukraine’s constricted exports is far greater. Since February 2022, the poor of the world have been significantly impoverished as they paid even higher food prices due to uncertainties about Russian and Ukrainian exports. The evidence to-date does not suggest that the war is the only cause of the recent higher prices, nor that it will cause the world to run out of grain, as some have suggested. It is, however, certain that every day that passes without the world having access to Ukraine’s current stocks, the crops it is now harvesting, and any future year crops lost to a war-diminished capability to produce and export needed food, food prices will likely remain high. And as they do, they continue to contribute to a slow-walk towards impoverishment and multiple humanitarian tragedies.